Our Vision and Mission

To ensure freedom and justice for all kids, systems must be responsive to how gender and sexism intersect with racism to drive youth incarceration.

The Vera Institute of Justice (Vera) believes that we can end the incarceration of youth on the girls’ side of the juvenile justice system by building stronger, safer, and more equitable communities where girls and lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and gender-nonconforming (LGB/TGNC or “gender expansive”) youth—particularly youth of color—are no longer criminalized for the violence and discrimination they face.

Through its Initiative to End Girls’ Incarceration, Vera is zeroing out the country’s confinement of girls within 10 years. We are inspiring and partnering with jurisdictions to build new reforms and programs that will better support the safety and well-being of girls and gender expansive youth in their communities, address the root causes of their incarceration, and permanently close the doors to girls’ juvenile detention and placement facilities.

Getting to Zero

Getting to zero girls in 10 years is ambitious but achievable. Juvenile justice reforms have already reduced the annual number of girls’ detentions to less than 46,000 nationwide.[]Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, “Census of Juveniles in Residential Placement,” https://www.ojjdp.gov/research/CJRP.html. In 2015, most states had fewer than 150 girls in long-term placement on a given day—many had fewer than 50.[]Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, “Census of Juveniles in Residential Placement,” https://www.ojjdp.gov/research/CJRP.html. These reductions occurred even though the juvenile justice field has historically held a sharp focus on boys and left girls and gender expansive youth out of most reform discussions and investments.

The girls who remain in the nation’s juvenile justice systems do not belong there. Most have been locked up as a means to protect their safety or to address needs that have gone unmet in the community. Incarceration for these reasons cuts against best practices, and the girls who experience the harms of this confinement are disproportionately girls of color, LGB/TGNC, poor, in foster care, survivors of violence (especially family and sexual violence), and victims of sex trafficking.[]Lindsay Rosenthal, Girls Matter: Centering Gender in Status Offense Reforms, (New York: Vera Institute of Justice, 2018), https://www.vera.org/girls-matter; Francine T. Sherman and Annie Balck, Gender Injustice: System-Level Juvenile Justice Reforms for Girls (Portland, OR: National Crittenton Foundation, 2015), 31-32; Malika Saada Saar, Rebecca Epstein, Lindsay Rosenthal, and Yasmin Vafa, The Sexual Abuse to Prison Pipeline: The Girls’ Story (Washington, DC: Georgetown Law Center on Poverty and Inequality, 2015), 8-9 (discussing studies in South Carolina and California), https://perma.cc/V6K7-6VNQ; and Lindsay Rosenthal, “The Road to Freedom for Cyntoia Brown Was Much Longer Than 15 Years,” Vera Institute of Justice, March 5, 2019, https://www.vera.org/blog/the-road-to-freedom-for-cyntoia-brown-was-much-longer-than-15-years. The juvenile justice system is neither intended nor able to provide the long-term solutions needed to ensure the well-being and safety that they deserve.

The country is primed for change. #MeToo and #TimesUp have brought movements for gender and racial justice to the fore of national politics. Campaigns focused on accessing justice, safety, and freedom for girls and gender expansive youth of color have created momentum for progress. And, after decades of struggling with this smaller but unique population of incarcerated youth, justice and other child-serving systems are finally championing reform for girls and seeking help to better serve them.

Vera’s national Initiative to End Girls’ Incarceration is advancing gender and race equity by centering girls and gender expansive youth of color in juvenile justice reform discussions across the country and promoting gender-responsive systems change with the ultimate goal of getting to zero.

Our 10-Year Strategy

We aim to end the incarceration of youth on the girls’ side of the nation’s juvenile justice systems by 2029 through a three-pronged approach.

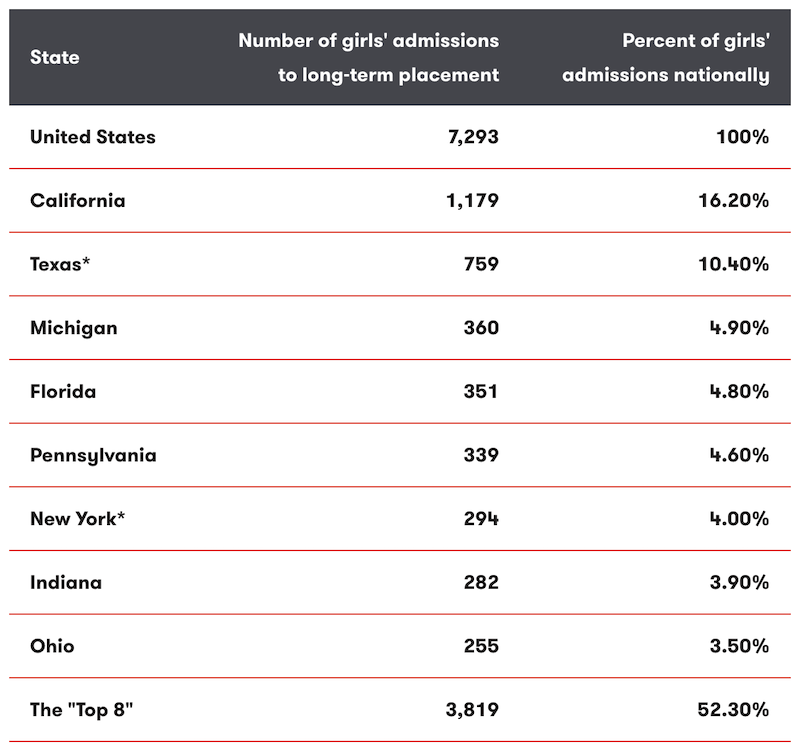

- Target the top incarcerators. Drive down numbers by targeting the top eight states that together account for more than 50 percent of the nation’s incarceration of girls.

- Target the lowest incarcerators. Inspire the collective imagination of the reform community by targeting states with exceptionally low numbers of girls that can get to zero quickly.

- Devise new solutions. Create an innovation network that can incubate solutions to some of the most intractable problems in girls’ incarceration to benefit the field. Pilot initiatives that employ our learning and test new approaches to these long-standing challenges.

Within each of these efforts, Vera propels justice actors to divert girls and decline to arrest, prosecute, or confine them, while also supporting strategic reforms and initiatives in other public systems that must address the root causes of girls’ incarceration.

Targeting the top eight incarcerators of girls to cut national numbers in half

In 2015, the top eight incarcerators (“Top 8”) of girls in long-term placement were responsible for incarcerating just over half of the roughly 7,300 admissions of girls to placement facilities across the country.[]M. Sickmund, T.J. Sladky, W. Kang, and C. Puzzanchera, “Easy Access to the Census of Juveniles in Residential Placement” (database) (2015), http://www.ojjdp.gov/ojstatbb/ezacjrp/. These states are the Top 8 incarcerators of girls by count, not per capita, as these are also some of the largest states. The Top 8 states were the same in 2013 and most saw modest drops in their numbers between 2013 and 2015. See full table for the counts of girls by state. One limitation to this data is that it is based on a point-in-time snapshot of girls in placement and does not capture flow of girls in and out of facilities. The actual number of girls admitted to placement is likely somewhat higher. National court data shows that dispositions to placement were approximately 11,000 nationally, but that number represents the number of girls’ court cases and not the number of girls; girls frequently have more than one case. Disposition data is not available by state so it is not possible to see how dispositions to placement are distributed. Three additional limitations include: (1) the counts of girls in placement cannot be compared perfectly across states because the dataset—OJJDP’s “Easy Access to the Census of Juveniles in Residential Placement”—counts only youth in the upper age of jurisdiction in a given state; (2) detention admissions are not available by state and the top detainers of girls could vary from those states that place the most girls; and (3) these numbers do not include young people tried as adults in the criminal system (however, evidence suggests that the number of girls tried as adults is quite small). California and Texas (the largest states) were significant outliers, together accounting for about a quarter of all girls’ admissions to placement.

*The age of juvenile court jurisdiction varies across these states, impacting what their total numbers would be. In 2015, the upper age limit of juvenile court jurisdiction in New York was still only 15 years, meaning that New York numbers would have been significantly higher if their juvenile system included 16 to 17 year olds.(In 2018, New York State raised the age of juvenile court jurisdiction from 15 years of age to 17 years of age.) In 2015, the juvenile justice systems in Michigan and Texas only included youth up to the age of 16, meaning their numbers for girls could have been also larger if they had raised the age (although the impact would likely not be as dramatic as that of New York).

Targeting the Top 8 would have an outsized impact: zeroing out girls’ incarceration in these states would cut numbers in half nationwide. Getting to zero in 10 years is also well within their reach. If the Top 8 states joined our mission, each would face very achievable annual targets for reducing girls’ placements. Vera is already working with cities and counties in five of these Top 8 states.

Targeting the lowest incarcerators to inspire and model reform

In several states, the number of incarcerated girls is so small that they could end girls’ incarceration altogether by closing their last remaining detention or placement facility or unit for girls. On the day of the last census in 2015, nine states—Alaska, Connecticut, Delaware, Hawaii, Maine, New Jersey, Rhode Island, North Dakota, and Vermont—plus the District of Columbia had 30 or fewer girls in placement.

Having some early leaders—states that actually get to zero—is critical to inspire other reformers. Helping these states get to zero is also of practical significance for the country. An entire population has never successfully been decarcerated before. Figuring out how to meet the needs of the last remaining girls within their communities demands that jurisdictions address some of the deepest and most complex issues driving youth into justice systems.

Vera is already working with four of these 10 jurisdictions.

Devising innovative solutions to intractable problems

All states and localities working to address girls’ incarceration face common challenges that have troubled systems for decades.

In addition to rooting sites in a common framework for understanding gender and its relation to justice, Vera provides jurisdictions with access to content and national experts related to some of the most pressing issues driving girls’ incarceration. Vera’s End Girls’ Incarceration Innovation Network builds on this by creating a peer-to-peer innovation network where jurisdictions can share best practices and incubate new approaches to shared problems.

But the field needs to invest in ideas—and test them. Vera is partnering with government agencies and community-based organizations across the country to pilot new and promising solutions to these long-standing issues. Beyond Vera’s proven process for generating gender-responsive cross-systems change, it is also creating model programs and services that the country can use to better serve girls and gender expansive youth.

An End to Girls’ Incarceration

It’s time we stop locking up girls. The practices behind the incarceration of girls raise significant equity concerns. The burden of incarceration is borne by girls and gender expansive youth of color who have been criminalized after child-serving systems have failed to meet their needs, and our juvenile justice facilities only do more harm. But the numbers are small and continuing to fall as more jurisdictions across the country are ready to face the gender and racial inequities within their systems and commit to real change. Vera is connecting these jurisdictions to each other and to advocates, research, national experts, new ideas, and investments to build a national effort that will end girls’ incarceration.

Endnotes

- Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, “Census of Juveniles in Residential Placement,” https://www.ojjdp.gov/research/CJRP.html

- Ibid.

- Lindsay Rosenthal, Girls Matter: Centering Gender in Status Offense Reforms, (New York: Vera Institute of Justice, 2018), https://www.vera.org/girls-matter; Francine T. Sherman and Annie Balck, Gender Injustice: System-Level Juvenile Justice Reforms for Girls (Portland, OR: National Crittenton Foundation, 2015), 31-32; Malika Saada Saar, Rebecca Epstein, Lindsay Rosenthal, and Yasmin Vafa, The Sexual Abuse to Prison Pipeline: The Girls’ Story (Washington, DC: Georgetown Law Center on Poverty and Inequality, 2015), 8-9 (discussing studies in South Carolina and California), https://perma.cc/V6K7-6VNQ; and Lindsay Rosenthal, “The Road to Freedom for Cyntoia Brown Was Much Longer Than 15 Years,” Vera Institute of Justice, March 5, 2019, https://www.vera.org/blog/the-road-to-freedom-for-cyntoia-brown-was-much-longer-than-15-years

- M. Sickmund, T.J. Sladky, W. Kang, and C. Puzzanchera, “Easy Access to the Census of Juveniles in Residential Placement” (database) (2015), http://www.ojjdp.gov/ojstatbb/ezacjrp/. These states are the Top 8 incarcerators of girls by count, not per capita, as these are also some of the largest states. The Top 8 states were the same in 2013 and most saw modest drops in their numbers between 2013 and 2015. See full table for the counts of girls by state. One limitation to this data is that it is based on a point-in-time snapshot of girls in placement and does not capture flow of girls in and out of facilities. The actual number of girls admitted to placement is likely somewhat higher. National court data shows that dispositions to placement were approximately 11,000 nationally, but that number represents the number of girls’ court cases and not the number of girls; girls frequently have more than one case. Disposition data is not available by state so it is not possible to see how dispositions to placement are distributed. Three additional limitations include: (1) the counts of girls in placement cannot be compared perfectly across states because the dataset—OJJDP’s “Easy Access to the Census of Juveniles in Residential Placement”—counts only youth in the upper age of jurisdiction in a given state; (2) detention admissions are not available by state and the top detainers of girls could vary from those states that place the most girls; and (3) these numbers do not include young people tried as adults in the criminal system (however, evidence suggests that the number of girls tried as adults is quite small).